One of the “foundations” (pun intended) of good millwright work is the machine is only as good as the base it sits on. When I started out as a millwright, the accepted practice was:

One of the “foundations” (pun intended) of good millwright work is the machine is only as good as the base it sits on. When I started out as a millwright, the accepted practice was:

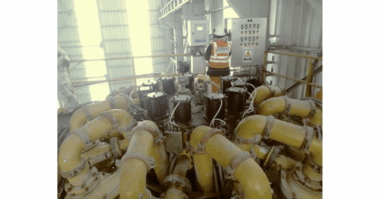

- The base should have sufficient mass to dampen vibration, absorb shock, and stabilize any forces from piping, duct, conveyors, or any other accessory components.

- The mass of the base should be at least 3 times the mass of the machine that it supports. In other words, if the machine weighs 1000 pounds, there should be 3000 pounds of base, to include base, frame, soleplate, grout/concrete.

- Unless the base sits upon isolators per design criteria, the base should be anchored with steel J-hook bolting, or some other attaching mechanism, to the floor.

If you see a machine with this kind of base today, odds are good that it was installed 30+ years ago. There are many various specifications for bases from organizations like API. Many companies use specifications given by their engineering design groups. But the actual installers may not know what the specifications are, and the commissioning engineer may not check it. Shortcuts are sometimes taken.

So that’s that got to do with alignment? A lot! Because you can’t align a moving target!

If the frame is not sufficiently rigid to prevent movement of the machine components during operation, the relative positions of the driving and driven machines can change. If the base has insufficient mass, the machines can move. If the base isn’t lagged into the floor, it can move. If piping and duct isn’t supported with suitable hangers, the machines must support their loads.

Simply stated, may not be able to perform a precision alignment on machines that sit on bad bases. And even if you get a great alignment, it could change.