Trust is the unseen ‘glue’ that binds together our social order. Trust is a vital element in relationships, in families, in sports, in business, in government and world affairs, or in virtually any facet of society where people interact and work together.

Business and Economics

The business workplace with all its various channels of communication operates on a platform of trust. Purchasing agents choose vendors they can trust. Individuals and businesses choose banks that they trust. Business executives deliberately align themselves with and choose people they can trust.

Co-workers trust the supervisor’s orders and carry them out. The supervisor trusts that his workers will let him know when a production device or tool is no longer capable of meeting a given performance standard. If trust were visible in the workplace, it would be seen everywhere that there are people.

Company management trusts that its employees are truthful in reporting. It is expected that accurate production results will be reported, even at risk of losing profits and bonus pay. Accurate, truthful reporting is not only a matter of internal trust, it can also affect how consumers and investors view the company. For a large publicly traded company, the value of trust, when compromised, can erase up to billions of dollars in stock valuation.

Loyalty to the firm is a huge factor. If an employee chooses to quit and work elsewhere, the trust factor is often damaged or even severed completely. It is not uncommon for this employee to receive his/her final paycheck immediately and possibly be escorted out of the building to his/her car.

A business’s financial controls and its standing with suppliers, creditors, stockholders, tax authorities, and customers are vital to maintaining confidence and viability. Businesses in good standing work diligently to maintain accurate accounting records. It is likewise vital that those with purchase authority and those who handle the company’s finances can be trusted.

In the early 1990’s, Barings Bank futures and options trader, Nick Leeson, created an ‘error account’ to hide a certain trading error made by a colleague in his department. He further used this ‘error account’ to cover other trading mistakes, but he found that with this account he could trade and make sizable profits to cover losses and even make healthy profits for Barings. Leeson’s ‘doubling’ strategy, essentially gambling with deposits, in January 1995 precipitously caused bank insolvency when the Great Hanshin earthquake in Japan caused Asian markets to tumble, crashing the value of Leeson’s trade positions. Untrustworthy financial actions, business-wise or personally, often have catastrophic consequences.

Government

The majority in government are doing honest work and are trustworthy individuals making worthwhile contributions. Unfortunately, there is a minority comprised of a few unscrupulous elected officials, appointed officials, and unelected bureaucrats who abuse their authority and spoil it for everyone. They peddle their influence to special interests, use their power to suppress specific individuals or groups, including the opposing political party, and even fraudulently tamper with elections. It is this minority that can give entire departments and branches of government a bad reputation.

It might be said that the formation of the United States was based on an abiding distrust of the King of Great Britain and his tyrannical rule over the American colonies. Following the American Revolution, the eventual U.S. Constitution document incorporated two novel characteristics of governing law: one, separation of powers and two, strict limitations of government infringement on citizens’ rights. It was a revolutionary break from and based upon utter distrust of rule by monarchy. The U.S. Constitution has survived 235 years. Those who know history can see today that its continuing survival will only be assured by educated citizenry and strong leadership of moral and ethical character.

Thankfully, engineers employed in government departments are largely separated from corrupt practices and direct political interference affecting their duties. Engineers, regardless of where they practice, must adhere to professional codes of conduct. The laws of nature and ethical codes of conduct pay no attention to organizational constructs.

Buildings and Bridges, Cars and Planes

In our modern industrialized society, public trust in what we, as engineers create and produce, is vital. We seldom put our attention on the large and complex building structures we enter, in terms of structural integrity, fire safety, water quality, HVAC systems, and so on. Likewise, we take for granted that the bridge we are crossing has been designed with ample margins of safety, is well maintained, and is structurally sound.

We routinely hop into our car and drive away without having to think about the brakes failing or the wheels coming off. In most vehicle transport situations, the trust factor, whether positive, neutral, or negative, is usually known and immediate.

Airline travel is statistically two to three orders of magnitude safer than travel by car, depending on the measurements used. Flight safety is primarily in the hands of the captain and the first officer. Most often these are people you do not know personally. There are necessarily many levels of safety and conservatism that go into airline travel. It must be this way because the consequences of mishaps often mean loss of life. Airline travel is built upon trust – the trust that engineers have produced a sound aircraft design, that it is properly maintained, and that skilled pilots will fly you safely from point A to point B.

A Profession Built on Trust

Engineering is generally regarded by the public as a trustworthy profession. With respect to form, function, and safety, engineering tends to align with the laws of nature. Engineering competence cannot be faked. Deviations from the natural laws, regardless of the design and manufacturing processes, often result in problems, premature failure, or accidents.

Several years back while I was engaged on a high-profile troubleshooting project, engineering colleague Tom Greene wisely commented that ‘mother nature performs the final design review.’ The outcomes of flawed engineering, or weak links in the design will sooner or later be visible to one and all. It might be said that engineering is a practice based on truth – the truth embedded in the laws of nature. Engineers tend to seek understanding in the natural laws that govern their work product. They learn to respect these natural laws and tend to work methodically and with an element of conservatism.

Larger scale engineering projects are often carried out in teams. Its members rely upon each other for technical design support. In larger organizations formal design review processes are established by protocol and policy. The benefits in terms of product marketability, performance, reliability, and safety are often worth the added time and manpower costs. In such an environment, team members, and the organization all benefit from this close professional coordination and mutual trust.

Trust is earned. It comes with keeping one’s word, being honest even when ‘inconvenient’ to do so, conveying information accurately and truthfully without omitting important relevant facts, and making decisions that consider all parties involved.

Figure 2. Not unlike mountaineering, engineering teamwork involves mutual trust.

Trustworthiness is a way of life. It encompasses more than just your work. Your manners, what you say, the products of your work effort, the way you conduct your personal and business affairs, and the people you associate with all contribute to what others think about your trustworthiness. It is an intangible, yet observable image that others see in you. Believe me, others do observe and some of them may see more about you than you imagine. They form opinions. Is this a form of profiling? In a way it is. But realize it is a powerful survival mechanism. It works both ways. It is pro-survival for both the person who is trustworthy and for the person who can observe behavior in others.

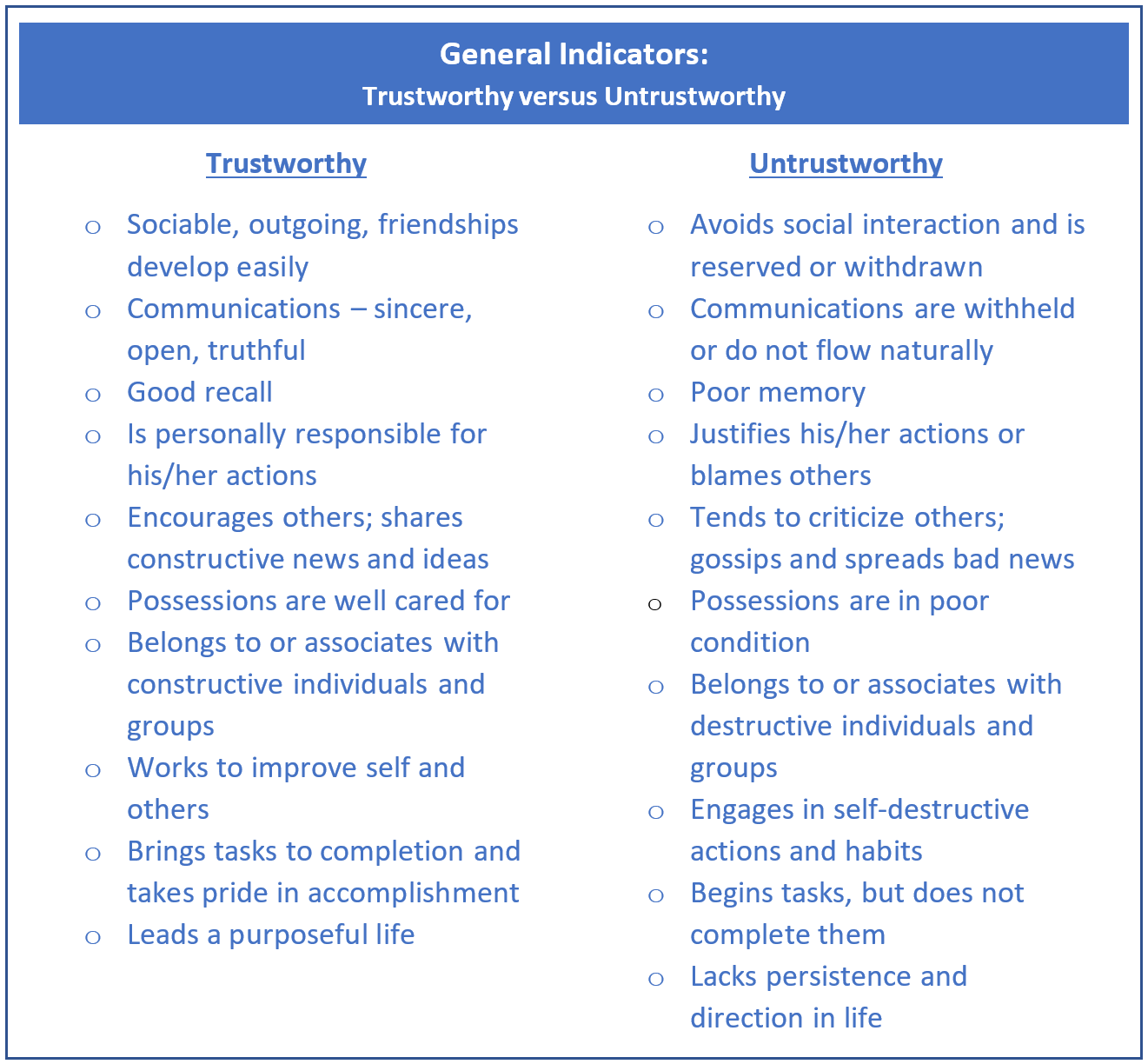

Table A provides a list of general indicators of trustworthiness versus untrustworthiness. It must be emphasized that these are not to be taken as absolutes. A trustworthy person may exhibit a few characteristics in the ‘Untrustworthy’ column and vice versa. For example, ‘Poor memory’ can be related to medical health and not to one’s social character. Another example would be ‘Begins tasks but does not complete them.’ Many have this proclivity to a greater or lesser degree. Some of it could relate to those you live or work with. On the other hand, we’ve probably observed people who apparently lack the ability to complete just about anything, once started. Possessing a number of traits in the ‘Untrustworthy’ column is probably a reliable indicator of character.

Avoid profiling people based on just a few column characteristics. The value of Table A is perhaps more to heighten your awareness of both self and others with respect to trust. Trust your own instincts. Anyone who’s owned a dog knows that its instinctual knowledge of human character, including trust, is amazingly accurate. There is no logical or rational explanation for this. The dog just knows. When it comes to the semi-intangible quantity of trust, likewise, you yourself know best.

A person’s character cannot be artificial or faked. Trustworthiness, by definition, cannot be pretended. Be real. Live with the truth. Live a life of personal integrity and be trustworthy.

Read Ethics and the Engineer in Practice – Part 1 and Part 2.