When it comes to gasket applications, heat exchangers are among the most difficult pieces of equipment to seal. These are complicated pieces of equipment that require special gasketing attention for proper safety and maximum efficiency.

When you are having issues with heat exchanger gaskets, there are four major areas to consider:

- Heat exchanger design: Because of the wide variety of heat exchanger designs and gasket applications, achieving the correct gasket stress can be tricky. Do you have enough stress from the flange design to create a seal?

- Assembly: Is the compression force enough or too little? Do you have the right gasket?

Condition of metal faces: Are the flange faces uneven, damaged, corroded, dirty, or not as specified? - Gasket material: Are you re-using old gaskets? Or using a gasket with incorrect dimensions or one that is extruding?

This post examines each of these areas in detail to help you identify heat exchanger gasket issues quickly and take the right corrective steps early for maximum safety and performance.

Heat Exchanger Design & Gasket Stress

Heat Exchanger Design & Gasket Stress

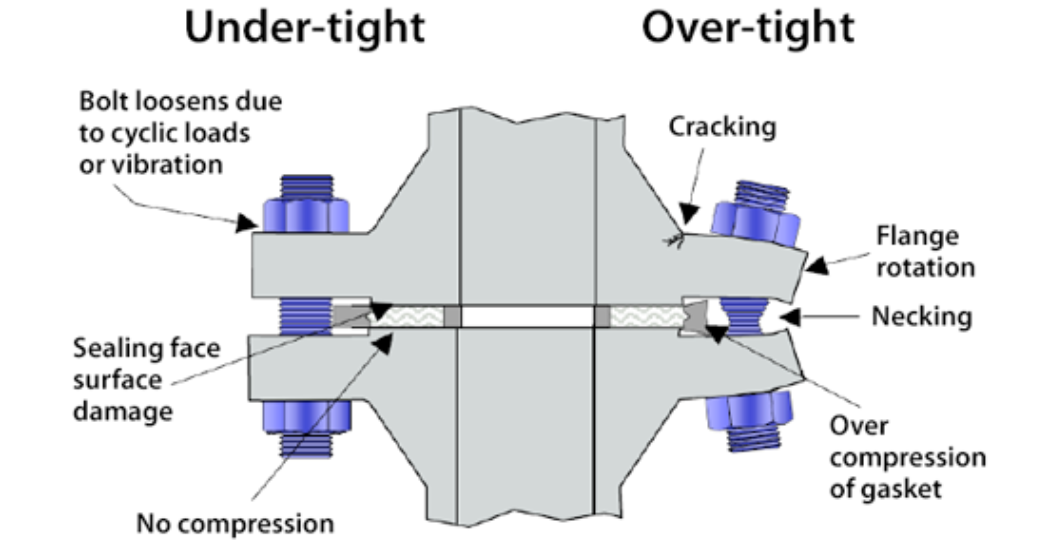

Because of the wide range of heat exchanger designs, insufficient or excessive gasket stress is a common issue. Insufficient stress may be caused by gaskets that are too wide. The answer to this issue is to narrow the gasket that will result in higher seating stress and better sealing. Many heat exchangers with poor seating stress can only be fixed by looking at the measurements and calculating the stress.

With excessive gasket stress, you may have too much bolt load resulting in damage of the graphite sealing element. In this case, the best solution is to lower the stretch of the bolts and possibly even change the bolting material to one that has more stretch at a lower yield.

Gasketing Assembly

It’s important to consider issues with gasket installation, including:

- Incorrect/insufficient bolt tightening: This can be the result improper or inaccurate torquing procedure.

- Operating temperature: Can be an issue when you exceed the temperature limit of the gasket. Check the gasket specification for maximum allowable temperature.

- Bad threads/insufficient thread length: Ensure that nuts are a good running fit over the entire length of the bolt thread and that threads are long enough to allow nuts to make contact with the metal faces. Remember to have enough thread to always have a hardened flat washer. If bolt is too short, replace with a longer one.

Metal Flange Faces

Metal Flange Faces

Flange faces are the sealing areas of the flange. They are mated together when the flange is bolted up, and the gasket is compressed between them. There are several important areas to check to ensure optimal performance:

Flange Surface: Always check the texture of the flange surface. Concentric grooving is ideal for high pressure. Where phonographic or continuous spiral groove is used, the depth must not be too deep for the gasket to fill. Make sure there was no damage in transit or changes from the specified order. Mobile machining technology can be used to get the optimal face conditions.

Uneven Faces: This may mean that the flanges are too thin. Remember that faces should always be sufficiently rigid not to be distorted by bolt load. Flange faces should also always be parallel and bolt load should never be relied upon to pull flanges together. Bolts should be tightened in proper sequence as noted above to prevent “cocking.”

Damage/Dirt: Every attention should be given to ensure that faces are clean, flat, and free from imperfections too deep for the gasket material to completely fill. Care should be taken in removal of old gasket material. While it should be completely removed, overzealous cleaning could damage the metal surface. Faces should be wire brushed down to clean metal, and serrations should be perfectly clean.

Gasket Material

There are many ways in which the gasket condition and material can have an enormous impact on performance and safety:

Loss of resilience/contact with faces: Are you re-using old gaskets? THE RE-USE OF GASKETS IS HIGHLY DISCOURAGED. Especially with heat exchangers, re-using old gaskets can lead to serious and dangerous safety issues. The older gasket will have hardened and can no longer be relied upon for safe sealing. Furthermore, the initial cost of a new gasket is far less than any downtime costs to replace an old, faulty gasket.

Rapidly deteriorating gasket material: This likely means that the gasket material is incompatible with the contained fluid/temperature. Recheck material recommendations (chemical compatibility) and select an appropriate gasket.

Extrusion: If the gasket is extruding from the faces, this likely means excessive use of jointing compounds. Unless specified, the use of compounds and paste is not recommended. These act as lubricants which reduce friction between the gasket and the metal facings and thereby reduce the load bearing properties. Where non-stick finish is required, it can be applied during production of the gasket material.

Incorrect dimensions: Gaskets should always have clean cut edges slightly larger than that of the vessel or pipe; that is, the gasket should not protrude into the flow path of the fluid. If it does there is a design or manufacturing error that needs to be corrected. Protrusion could create turbulence in addition to restricting flow. The gasket could also suffer damage through erosion by the fluid. Providing the gasket is compressed over the entire face, there is little likelihood of absorption of the fluid. Black holes should be sufficiently large to allow a clearance around the bolts.

For more information or for assistance with a specific application, contact Chesterton today to learn more about their heat exchanger sealing solutions.

Free Download: Chesterton’s Flange Sealing Guide — Basics & Best Practices

Learn best practices for gaskets and bolted connections including:

• Jointing methods

• How to select the proper gasket

• Factors affecting bolted joints

• Gasket test standards

• Sealing considerations based on heat exchanger types

• Installation/disassembly procedures

• Sample Heat Exchanger Data Collection Sheet

About the Author

Ron Frisard is Field Product Manager of Packing & Gaskets for A.W. Chesterton Company. He has worked for Chesterton for 27 years in all facets of valve and pump packing. Ron has presented at many conferences including the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI), the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME), and Valve World in Europe and America. Ron is also currently the Vice Chair for both the Packing and Gasketing divisions of the Fluid Sealing Association (FSA).