Author: Henri Azibert

When we think of “legacy”, we often look at cathedrals, temples, and castles that were erected centuries ago. We rarely think of infrastructure projects, as they are most often deep underground or hidden behind tall fences. Yet, much of our endeavors reside in the great projects of cooperative human activity designed to shape our environment to meet our needs. Certainly, water and waste water transport is often ignored, yet it is evidence of major human accomplishments.

Population increases the need for clean water and disposal of waste water grows. Pipes are strewn throughout cities and connected to dwellings, but what goes in must eventually come out; so an effluent flow is channeled out for treatment before being released into river ways and eventually to the ocean. While some regions have dry climates and must import water, others have too much and must get rid of it. Unfortunately, these imbalances seem to only be intensifying. This is why water is routed from Northern to Southern California, and why monumental pumping systems have been built to extract water out of lake Pontchartrain in Louisiana.

When possible, the easiest way to get the water to its destination is to use gravity; a natural downward-sloping conduit will achieve this best and over long distances without having to use power. However, when the end point is at a higher elevation than the source, pumps must come to the rescue.

As a participant in the design and building of these systems, I must offer a few guiding principles worth considering.

Depending on the society you have the luck or misfortune to be working in, you will have the chance to either contribute to a great success or engender nothing but problems for, or cursing from, those who use a deficient system.

Although it would be comforting to ignore for a moment the constraints of budgets, competitive bids, demagogic debates, and wishful thinking, they must unfortunately be dealt with. The first hurdle is to overcome the short-sighted selfish practices of wanting to get more out than you put in…the directives to get more from less. They are yet another aspect of an attempt to violate the law of conservation of matter and energy. This is where engineering knowledge can be used to confuse the decision-makers to achieve the right goals despite the misguided direction. Unfortunately, having to deal with politics can be as much work as doing the actual project, but providing the right vision and convincing others to embrace it is an essential step.

When designing the system, there is a need to plan for the distant future. It is useless to plan for current needs as they most likely were grossly underestimated. Even if adequately assessed, they will be exceeded by the time the system is built. Planning for the needs of when the system will come online is also insufficient as systems will be utilized long past their stated design life – by decades, even centuries! Design to specifications, but also to the unexpected. General trends must be taken into account: speed, pressure, temperature, and output will need to increase at some point over the life of the system.

For equipment, it should last past the designer’s career (if not lifetime). Designing to last is straightforward: test way beyond the duty requirement, then fix every problem you encounter. Eliminate wear by using the right materials. Eliminate deflections and flexing. Oversize the cooling capacity and the lubrication system. Noise and heat are sources of waste; when encountered, they should be reduced. Stay away from cavitation, mixed flow, or restrictions.

Plan for ‘ease of maintenance’, and as much as possible, reduce it to a minimum. Keep in mind that conditions will change, material availability will disappear, and knowledge will be lost. Also know that improved newer materials will be discovered, developed and applied. There likely will be the possibility for the retrofit of more efficient drivers, advanced hydraulics, and more effective sealing solutions. The challenge is to plan for the equipment to be maintained so it will perform better than when new.

We are also in an exciting time where controls and connectivity are allowing the remote monitoring of systems and prediction of needed maintenance. With further advances we can expect systems to adapt themselves to the changing conditions and even to become self-maintaining. Eventually the lifetime of a major infrastructure project will no longer be limited by neglect. The systems will no longer deteriorate, they will only end when their function no longer exists. The prospect of long-lasting legacy has never been so much within our reach, and duty.

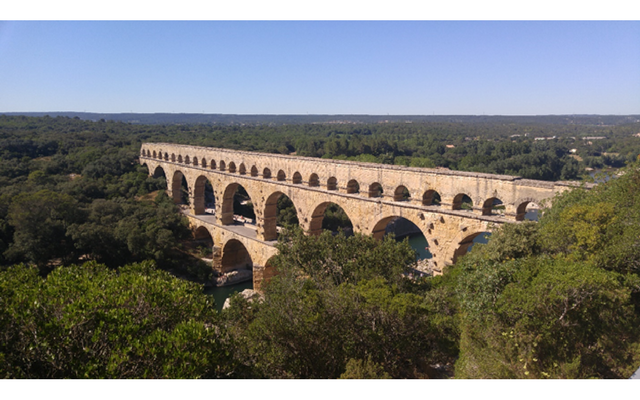

Although not all water infrastructure projects will survive as long as the Pont du Gars, which brought water to the citizens of Nîmes from Uzès, we should admire it and use it for inspiration. It was used for four centuries and still stands as a monument to the Roman engineering expertise two millennia after its construction.

Infrastructure Week is May 14 – 21, 2018. Follow along using the hashtag #TimeToBuild.