Author: Robert X. Perez, Machinery Engineer

Introduction:

In my second installment, I explained how the ideal gas law can be used to convert gas volumes from one set of process conditions to another. Now, we will continue the discussion of gas flow conversions, but I will go one step further by explaining the importance of the compressibility factor (z) when process conditions become more and more extreme.

Compressibility Factor (Z)

Keep in mind that the flow conversion equations presented above assume you are dealing with an ideal gas. In general, deviation from ideal gas behavior becomes more significant the closer a gas is to a phase change, the lower the temperature, or the higher the pressure. The compressibility factor (Z), also known as the compression factor, is the ratio of the expected volume of a gas to the volume of an ideal gas at the same temperature and pressure. The compressibility factor is a useful thermodynamic property for correcting the ideal gas law to account for the gas applications encountered in the real world.

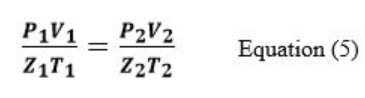

If we insert the compressibility term into equation 1, we get:

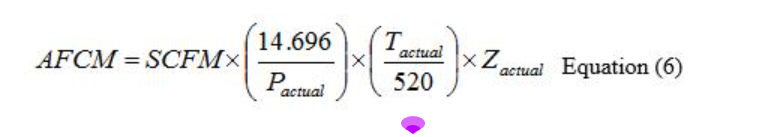

After a little manipulation of equation 5, we arrive at the ACFM equation with the compressibility factor z:

Let’s look briefly how the compressibility factor changes as a function of pressure for natural gas with a specific gravity of 0.6 (Table 1). Notice that for z to significantly reduce the idealized flow, the pressure must exceed 1000 psia for natural gas at 100 oF. As a rule of thumb for natural gas, we can say that z will only vary from 1.00 only a few percent if your suction pressure is only a few hundred pisa. However, if your suction pressure is much greater than a few hundred psi, you need to include z in your calculation of the ACFM.

Table 1: Compressibility Factors for natural gas with a specific gravity of 0.6

| Suction Pressure (psia) | Compressibility Factor (Z) at 100 oF |

| 0 | 1 |

| 100 | 0.99 |

| 200 | 0.975 |

| 300 | 0.962 |

| 400 | 0.95 |

| 500 | 0.94 |

| 600 | 0.93 |

| 700 | 0.92 |

| 800 | 0.908 |

| 900 | 0.9 |

| 1000 | 0.89 |

| 1100 | 0.88 |

| 1200 | 0.87 |

| 1300 | 0.862 |

| 1400 | 0.857 |

| 1500 | 0.85 |

| 1600 | 0.84 |

| 1700 | 0.8375 |

| 1800 | 0.83 |

| 1900 | 0.8275 |

| 2000 | 0.82 |

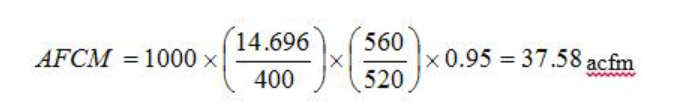

If, for example, we are moving 1000 scfm of natural gas (S.G. =0.6) at 100 oF and 400 psia, then the corrected ACFM value will be:

Always remember that the compressibility factor is a function of pressure, temperature, and the actual type of gas being analyzed, which means you’ll need to get an accurate set of compressibility tables for gases you plan to analyze. The “GPSA Engineering Data” books contain very detailed compressibility tables for natural gas mixture.

With time, these equations will become second nature to you as you apply them to you real-world applications. You will eventually come to understand the relationships between volumetric gas flow, pressure and temperature. Next time someone asks you how much gas flow will you need, ask them: Do you want the flow in SCFM, ACFM, or ICFM?

About the Author:

Robert X. Perez has over 30 years of rotating equipment experience in the petrochemical industry. He earned a BSME degree from Texas A&M University (College Station), a MSME degree from the University of Texas at Austin, and is a licensed professional engineer in the state of Texas. Mr. Perez served as an adjunct professor at Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi, where he developed and taught the Engineering Technology Rotating Equipment course.

Robert X. Perez has over 30 years of rotating equipment experience in the petrochemical industry. He earned a BSME degree from Texas A&M University (College Station), a MSME degree from the University of Texas at Austin, and is a licensed professional engineer in the state of Texas. Mr. Perez served as an adjunct professor at Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi, where he developed and taught the Engineering Technology Rotating Equipment course.

He authored four books and coauthored four books in the field of machinery reliability. Mr. Perez has also written numerous machinery reliability articles for numerous technical conferences and magazines.