When it comes to dynamic sealing, the “best solution” is not always the “right solution.” Economics play heavily into seal selection. A user must weigh the benefits of reduced leakage –improved efficiency, reduced emissions, and/or increased reliability – against the cost to purchase and install the seal. Brush seals, a proven technology carried over from aerospace developments, provide one cost effective means to upgrade sealing in turbomachinery.

Dynamic seals generally fall into one of two product families: rigid geometry seals or compliant geometry seals. When a rigid geometry seal makes contact with the rotor – an event known as a “rub” – it typically results in the permanent removal of effective sealing material, increasing leakage. In contrast, compliant geometry seals track rotor movement with minimal loss of effective sealing material when a rub is experienced. The machine returns to steady state performance with minimal increase in leakage.

Brush seals fall into the category of compliant sealing. Densely packed bristles bend with rotor contact, giving brush seals an innate ability to follow rotor movement with minimal wear. Brush seals can be particularly effective in reducing leakage gaps that occur from large thermal differences between rotating and stationary components and/or from significant radial movement of the rotor.

Large gas and steam turbine applications commonly employ brush seals to reduce the leakage gap experienced with labyrinth seals – increasing operational efficiencies. In general purpose steam turbines, brush seals enhance the performance and longevity of carbon rings.

The use of steam generation to support operations is commonplace in many refineries, petrochemical plants and food processing centers. Where different processes require different steam conditions, steam pressure may need to be knocked down from one process to another. The simplest solution is to use a pressure-reducing valve, but a more efficient alternative is to do some work with the available energy. A general purpose steam turbine does just that. The turbine knocks down steam pressure by converting it into rotational energy to drive a small pump, a compressor or other equipment. General purpose steam turbines are typically classified with output ratings below 3500 hp (2.6 MW).

CONVENTIONAL CARBON RINGS

Conventional gland sealing in general purpose steam turbines is accomplished with carbon rings. A carbon ring comprises three segments held together with a garter spring. Typically, the steam end and exhaust end gland boxes each carry four to five carbon rings, though there may be more. Unlike labyrinth seals, carbon rings are not rigidly mounted into a turbine’s casing; the segments are installed on the turbine’s rotor in a gland pocket.

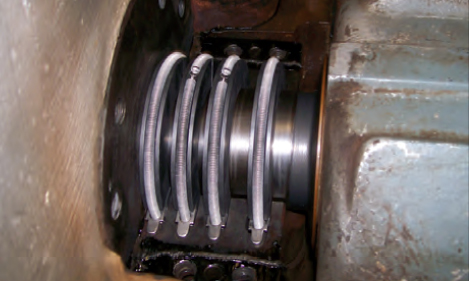

Typical gland box outfitted with conventional carbon rings

Carbon rings have two sealing surfaces: a face seal to the downstream wall of the gland pocket and a shaft seal to the rotor surface. The face seal prevents steam from going around the carbon ring while the shaft seal, the ring’s inner bore, controls steam leakage along the turbine’s rotor. Over time, wear to the carbon bore opens its shaft clearance, causing steam leakage to increase. This increase in steam leakage negatively affects operational costs as well as maintenance costs. Leaking steam can flow into the bearing sump, contaminating the lubricating oil, or thermally increase bearing oil temperatures. Oil contamination and higher oil temperatures will degrade bearing performance and increase the potential for bearing failure. In addition, the natural composition of carbon can break down in a steam environment, which can result in excessive leakage and subsequent erosion of the gland box.

Sentinel® Floating Brush Seal

APPLYING THE BRUSH SEAL

The incorporation of brush seal technology into general purpose steam turbine carbon rings mitigates carbon wear at the rotor interface and significantly reduces steam leakage. This hybrid solution is the Sentinel® Floating Brush Seal (FBS) from Inpro/Seal®. The Sentinel FBS utilizes brush seal technology as the primary shaft seal while a carbon ring provides face sealing in the gland box. The combination of the two technologies provides a robust and self-centering assembly that is a drop-in replacement for conventional carbon rings. With the brush seal technology on the upstream side of the gland box, the bristle pack reduces the pressure on downstream seals while acting as a natural excluder to filter out steam contaminants. The added benefit with a brush seal is prolonged seal life and a lower, more stable leakage rate. “The Sentinel Floating Brush Seal not only reduces steam leakage and bearing oil contamination, it also reduces the erosion we typically see inside the gland box when end users have steam purity issues,” explains Michael Godzwon, Manager, Technical Support at Dresser-Rand.

The first floating brush seals for general purpose steam turbines were introduced to the marketplace in the early 2000’s to address complaints about carbon rings from equipment operators. A brush ring was contained in a stainless steel carrier, much like a brush seal for a jet engine. However, the all-metal construction of these first floating brush seals made them too heavy and the seals did not fl oat. The bristle pack wore out too quickly under the seal’s own weight. To lighten the assembly, a carbon ring was reintroduced.

The second generation floating brush seals – the hybrid solution described above – made their way into the market around 2007. This Sentinel FBS is a split design held together with a garter spring. The likeness to conventional carbon rings makes floating brush seals easy to install without having to remove the rotor and eliminates the need for costly casing modifications required by other seal technologies. Typically, two Sentinel FBSs are installed in each gland box. Downstream seals are replaced with new carbon rings.

Gland box upgrade with two Sentinel Floating

Brush Seals

LESS MAINTENANCE, LOWER LEAKAGE

Early adopters of the Sentinel FBS tested the seal’s capabilities on their most troublesome turbines. Wet steam conditions and cyclic operations were taking their toll on the carbon ring performance. The result was heavy maintenance and costly steam losses. One customer was changing out carbon rings every three to four months. Another had a visible condensate cloud after just four weeks. In both cases, the robustness of the Sentinel FBS was able to alleviate their problems. Maintenance intervals were extended to three to four years, steam leakage rates reduced by nearly 70%, and bearing oil temperatures reduced by as much as 27°C (80°F). The product’s success on these bad actors was the impetus for its two-year extended warranty.

Since these early successes, hundreds of the Sentinel FBS have been installed. The Sentinel FBS is available for a wide range of general purpose steam turbines, including Elliott, Dresser-Rand, Turbodyne, Terry, Coppus, Worthington and other makes.