This paper seeks to provide clear guidelines to readers about ways in which industrial lubricant degradation can be avoided. To do so, the author has set out to cover the fundamental information as it applies to industrial lubricants, their functions, and the concepts of degradation.

The six basic modes of lubricant degradation will be covered as well as various ways of identifying each of the modes and possible methods of managing each. In this section both field tests and observations will be noted as well as laboratory tests which can assist in determining the mode of degradation.

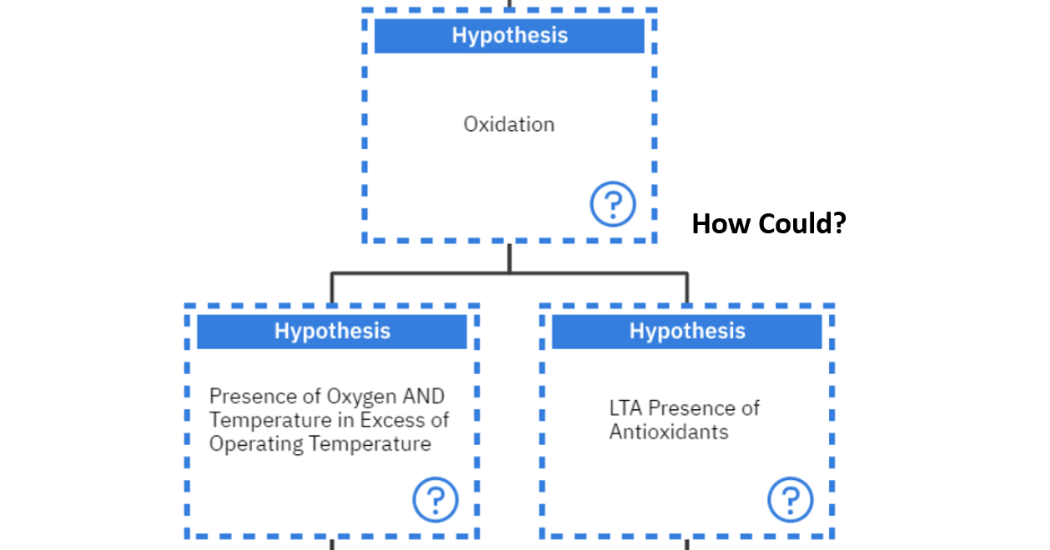

A closer look at one of the most popular degradation modes, oxidation will be covered which includes a logic tree for this mechanism. This logic tree will cover the physical, human and systemic / latent root causes for oxidation as it occurs in lubricants.

Information from global case studies will also be presented where lubricant degradation has occurred and measures that were put in place for their avoidance in the future.

1.0 What are the main functions of a lubricant?

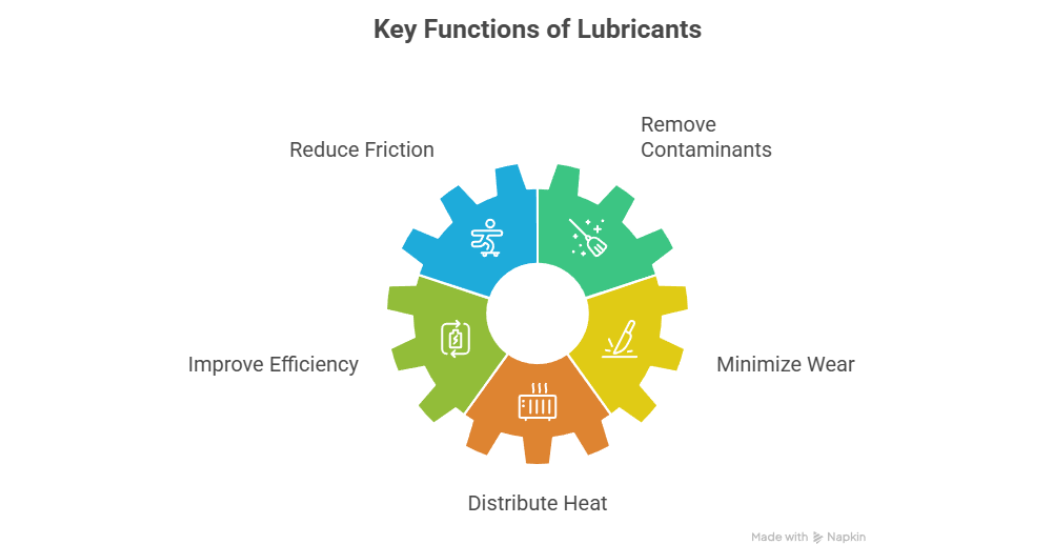

Degradation is a form of the lubricant failing its function. In fact, there are many functions of a lubricant and if something does not perform its intended function, then it has failed. Before discussing degradation, the basic functions of a lubricant must first be identified and understood.

There are five main functions of a lubricant; to reduce friction, remove contaminants, improve efficiency, minimize wear and distribute heat as shown in figure 1. These are not the only functions of a lubricant.

Depending on the application in which the lubricant is involved, it can adapt to various functionalities.

In hydraulic oil, the function of the lubricant is the transmission of power while for oil analysis, oil functions as a conduit of information. However, in each of its functions, it has the ability to protect the machine and its internals once it is in a healthy state.

From the moment that oil enters a machine, it will begin to degrade due to its sacrificial nature. Additives will deplete over time as they get used up and will no longer be able to protect the base oil and degradation will occur.

Figure 1: Key functions of a lubricant

Figure 1: Key functions of a lubricant

2.0 Lubricant Degradation

As noted above, lubricants are sacrificial in nature. They contain additives which are used to help protect the insides of the machines from corrosion, wear or to reduce the friction between these surfaces. There are also additives which help to improve certain characteristics of the oil through increased oxidation protection, improved demulsibility and aeration properties.

When a lubricant goes into service, degradation occurs as the additives are used up while the lubricant is performing its many functions. The challenge occurs when degradation reaches the point such that the lubricant is no longer able to perform its functions and fails. This is the outcome that everyone is trying to avoid.

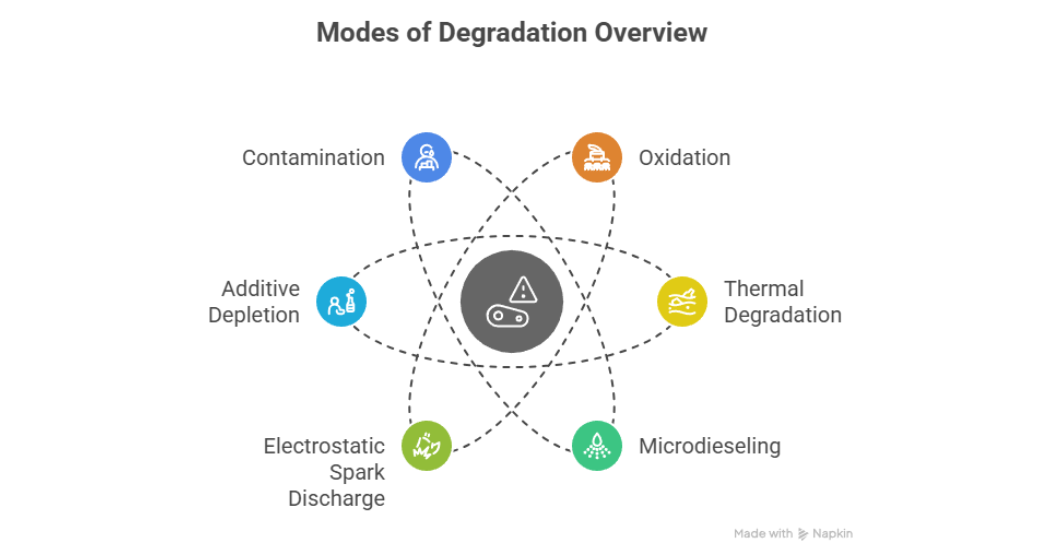

There are six modes of degradation which can be classified based on their environmental conditions and the deposits which form during those mechanisms as per Mathura S. (2021) shown in figure 2. These include; oxidation, thermal degradation, microdieseling, electrostatic spark discharge, additive depletion and contamination.

Figure 2: Modes of Lubricant Degradation

Figure 2: Modes of Lubricant Degradation

2.1 Oxidation

This is the most popular form of degradation or rather the one that has received the most attention. Quite often, it is used incorrectly to describe any form of degradation simply due to the lack of knowledge about the various other mechanisms.

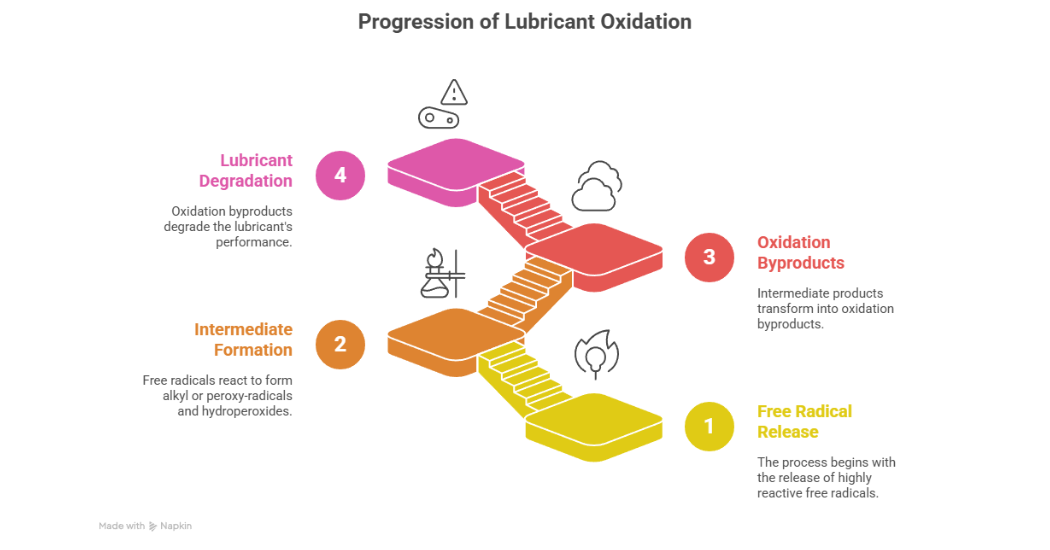

Oxidation occurs when there is a free radical released in the lubricant. These free radicals are quite reactive and propagate to form alkyl or peroxy-radicals and hydroperoxides. These eventually go on to form oxidation by products as per Ameye, Livingstone and Wooton, 2015 as shown in figure 3.

Figure 3: Progression of Lubricant Oxidation

Figure 3: Progression of Lubricant Oxidation

During oxidation, antioxidants are lost as they try to neutralize the very reactive free radicals. This is one of the key differentiators of this mechanism as it can help identify if it is occurring. Another key identifier is the production of varnish and sludge as the final result of this mechanism.

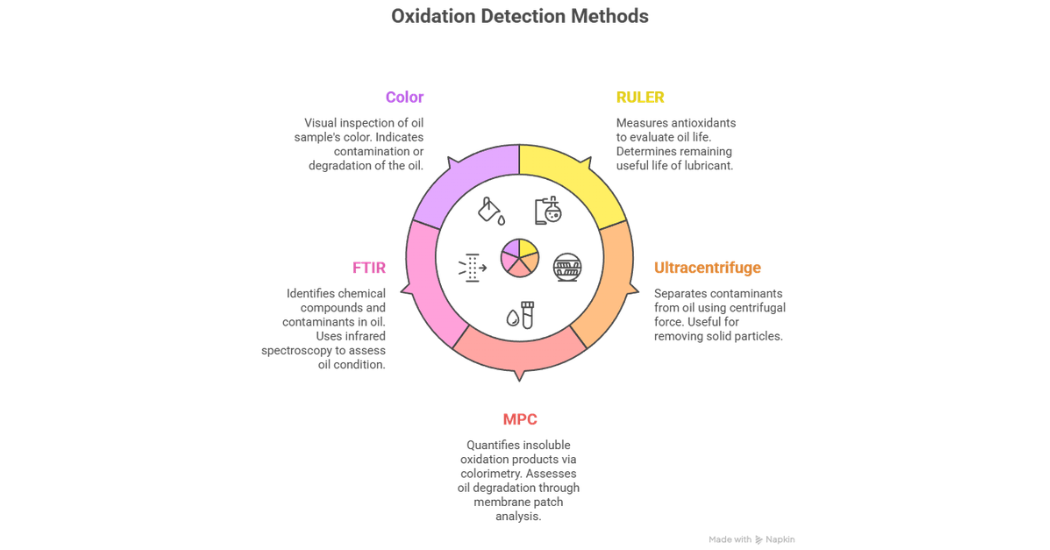

Some of the key tests to identify if oxidation has or is currently occurring include; RULER® (Remaining Useful Life Evaluation Routine) where the quantity of remaining antioxidants are measured,

Ultracentrifuge which gives an indication of the oils ability to form varnish, MPC (Membrane Patch Colorimetry) where a patch test is used to determine the oil’s ability to form varnish, FTIR (Fourier Transform Infrared) which gives an indication of the molecules present and colour which is not a very indicative test but can provide some guidance.

Testing for changes in viscosity and acid number will have some merit however, these changes are only prevalent after the antioxidants have significantly depleted. As such, these tests do not offer much warning to the operators and should not be used as early indicators. Some of these tests are shown in figure 4.

Figure 4: Tests for Oxidation

Figure 4: Tests for Oxidation

Another test which was not mentioned is RPVOT (Rotating Pressure Vessel Oxidation Test). While this is an industry standard test, it has a low rate of repeatability which means that the same oil undergoing the same test will produce varying results and these results are not easily quantifiable to operators as the value is given in minutes. Hence, it is not a preferred test to perform when determining if oxidation is present.

2.2 Thermal Degradation

This mechanism is often confused with oxidation but they are very different. For this mechanism to occur, the lubricant should experience a temperature of above 200°C. At these temperatures, the lubricant is cracked as this exceeds its thermal stability point.

During this process, the shearing of molecules occurs which eventually leads to polymerization and a decrease in viscosity. In oxidation however, there is an eventual increase in viscosity. This is one differentiating characteristic.

As the molecules are sheared, there are two processes which occur in the lubricant during thermal degradation. These small molecules will cleave off and either volatize or become condensed. When they are volatized, they do not leave any deposit. However, if they become condensed then dehydrogenation occurs (in the absence of air) and coke is formed as the final deposit. There can be other deposits which occur between the start and completion of the process.

The two key differentiators between oxidation and thermal degradation is that oxidation experiences an increase in viscosity and produces sludge or varnish as the final deposit while thermal degradation experiences a decrease in viscosity with lacquer and carbonaceous deposits as the final results.

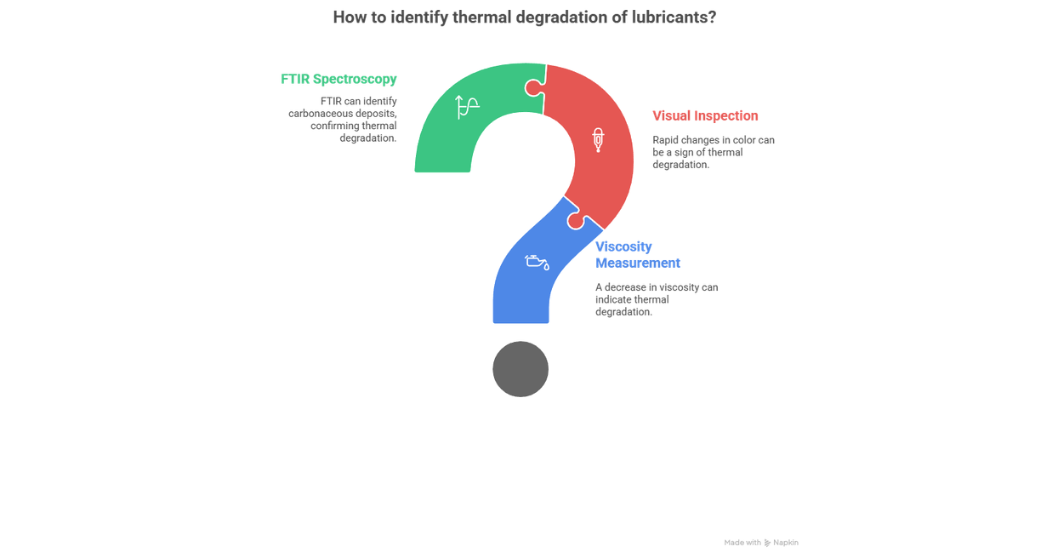

There are a few lab tests which can help in the identification of Thermal Degradation which include; a decrease in viscosity (around 5%), rapid changes in colour and the use of FTIR for identifying the presence of carbonaceous deposits as shown in figure 5.

Figure 5: Lab tests for Thermal Degradation

Figure 5: Lab tests for Thermal Degradation

2.3 Microodieseling

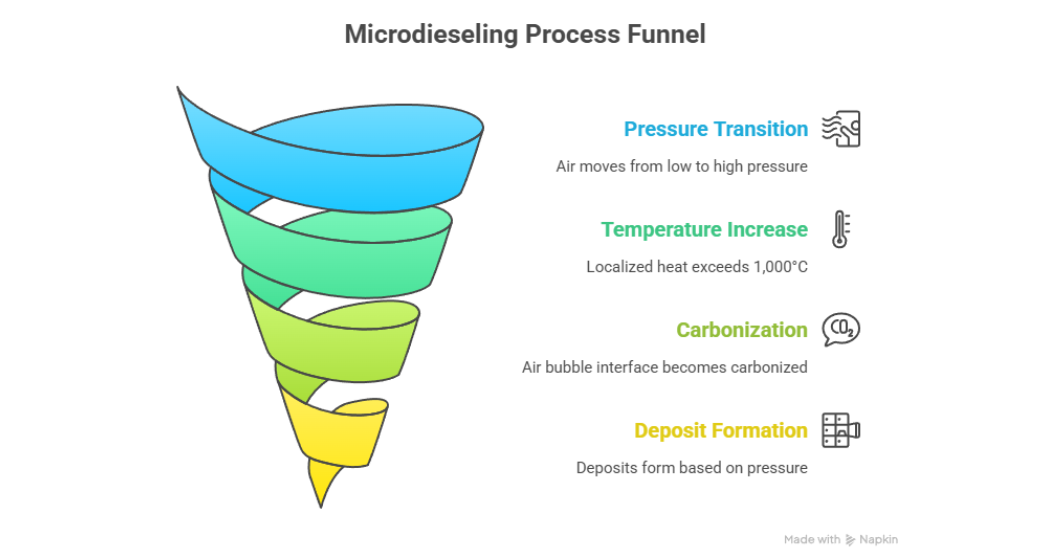

This mechanism is very similar to cavitation experienced in pumps except it occurs within the lubricant. Microdieseling is also known as compressive heating and can be considered a form of pressure induced thermal degradation.

During microdieseling, air entrained in the oil transitions from a low-pressure zone to a high-pressure zone. This produces localized temperatures in excess of 1,000°C. At this temperature, the interface of the entrained air bubble becomes carbonized and the oil begins to darken rapidly.

There are two main conditions which can occur during microdieseling either, a low flashpoint with low implosion pressure or a low flash point with high implosion pressure. Both will produce different types of deposits.

For a low flashpoint with low implosion pressure, this ignition produces incomplete combustion products such as soot, tar, and sludge. For a low flashpoint with high implosion pressure, these products experience adiabatic compressive thermal heating degradation and produce varnish from carbon insoluble including coke, tar, and resins as seen in figure 6.

To confirm the presence of microdieseling, one can perform a physical inspection of the components. Due to the small explosions of the entrained air, one will see a surface resembling small pits similar to cavitation. FTIR can aid in confirming the presence of the aforementioned by-products (coke, soot, tar, sludge, resins).

Figure 6: Microdieseling Process Funnel

Figure 6: Microdieseling Process Funnel

2.4 Electrostatic Spark Discharge

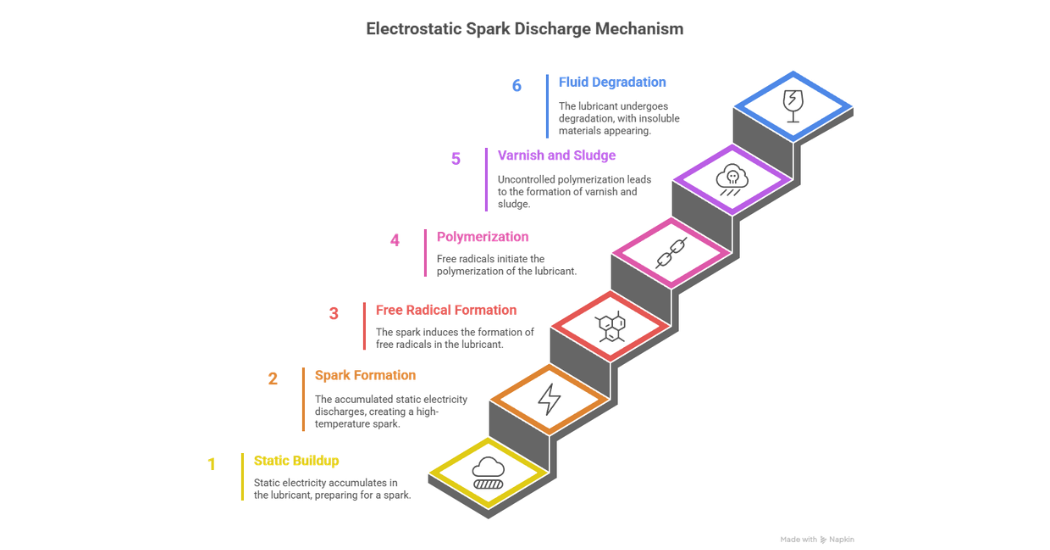

Static electricity is not just confined to our immediate environment, it can occur at a molecular level as well. In a lubricant. static electricity can build up to a point where it produces a spark. This spark can induce temperatures in excess of 10,000°C.

There are three main stages of this mechanism. In the first stage, the static electricity builds up to produce a spark. Next free radicals are formed which contribute to the polymerization of the lubricant.

Finally, this leads to uncontrolled polymerization which produces varnish and sludge which can either remain in solution or be deposited. During this final stage one can also see elevated fluid degradation and the presence of insoluble materials as indicated in figure 7.

One can perform a physical inspection of the filter membranes of the equipment to verify if electrostatic spark discharge has occurred as one will notice small burnt patches on the membrane. These are the areas in which the spark occurred after the build up of static electricity and discharged on the filters.

FTIR and QSA (Quantitative Spectrophotometric Analysis) can aid in identifying the presence of varnish, sludge or other insolubles. The RULER test can also identify remaining antioxidants after the free radicals were released which they will try to neutralize.

Figure 7: Electrostatic Spark Discharge Mechanism

Figure 7: Electrostatic Spark Discharge Mechanism

2.5 Additive Depletion

Additives are placed in the oil as a sacrificial component to protect the oil. However, if they deplete too quickly, this can be a form of degradation as the oil can no longer perform its intended function. When the additives deplete there are two types of deposits which form: organic and inorganic.

Organic deposits are the rust and oxidation additives which drop out of the oil. These react to form primary antioxidant species. On the other hand, inorganic deposits are the additives which dropped out but did not react with anything in the oil. These are usually the ZDDP (Zinc dithiophosphate) additives used as antiwear or antioxidants.

Some tests which can be performed to determine if additive depletion has occurred include; FTIR (which will determine the presence or absence of particular molecules), Colour (various additives have particular colours) and RULER (determines the remaining antioxidants in the oil).

2.6 Contamination

This type of degradation mechanism does not get much attention as some may not consider it to be a degradation mechanism. On the contrary, the presence of contaminants in an oil can actually lead to three varying degradation mechanisms, namely; oxidation, thermal degradation or microdieseling.

Contamination can be defined as any material that is foreign to the lubricant. These are usually classified in three categories; metals, air or water. These contaminants can also act as catalysts to increase the rate of degradation.

The lab tests used to confirm the presence of contaminants include colour (as defined by laboratory guidelines), presence of water or fuel (which gives the indication of a foreign material) and FTIR which can help in identifying the molecules present and whether or not they should be a part of the lubricant’s profile.

3.0 Factors affecting lubricant degradation

Lubricant degradation can occur in various mechanisms as noted above. While this paper will not go into details of avoiding each of these mechanisms, it will provide the reader with the knowledge to develop their own method of determining the real root causes to further put measures in place to avoid lubricant degradation.

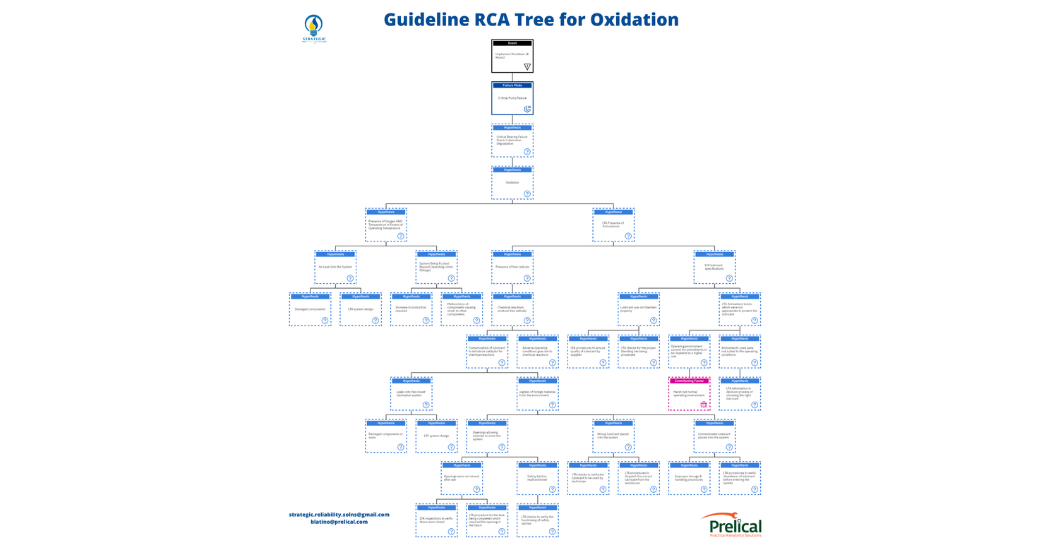

Based on global case studies, (Mathura, S. and Latino, R. 2022), the following logic tree was developed to assist users in determining the real root causes of oxidation. This tree will be broken up into several pieces before it is fully pulled together to allow the readers to get a full grasp of the method involved for these types of investigations.

Before this investigation begins, one must understand, “What is oxidation?”, “How can it occur?” and “How can it be identified?”. The answers to these questions can be found in section 2.1 above. The question remains, “How can Oxidation be prevented?” which will be investigated.

Essentially, this mechanism occurs due to the release of free radicals and can be identified / verified through lab tests such as RULER or MPC. To prevent its occurrence, one must perform a full Root Cause Analysis to ensure that all aspects have been investigated.

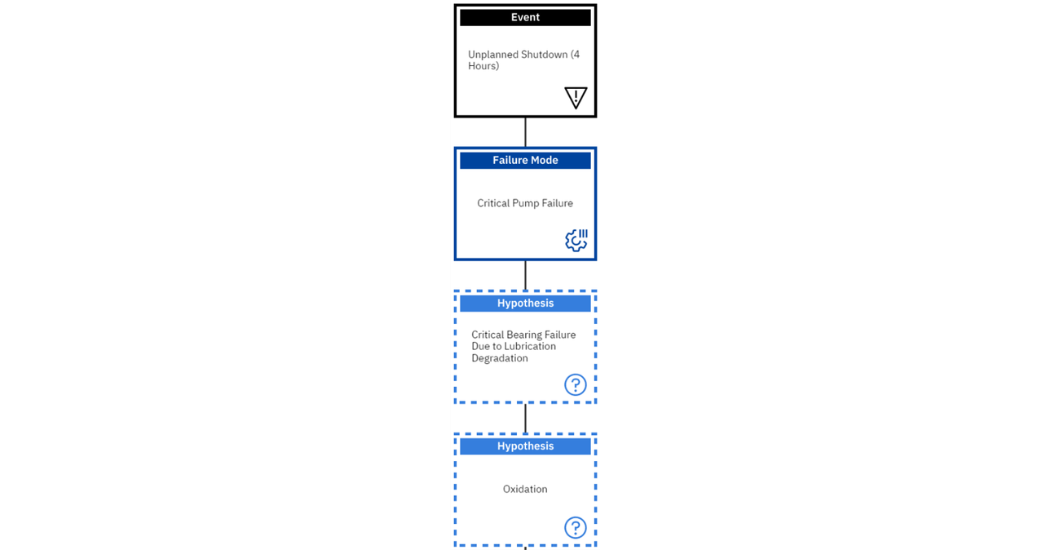

3.1 Building a logic tree for Oxidation

For any investigation to begin, there must have been a significant event, in this case, we will use the event of an unplanned shutdown which has a critical pump failure. In our hypothesis, we will investigate the reasons for the pump failure as it relates to a bearing failure which has experienced lubricant degradation. The beginning of our tree is shown in figure 8 below.

Figure 8: Beginning of logic tree for oxidation

Figure 8: Beginning of logic tree for oxidation

In a real event, one would have to hypothesize that all the six degradation mechanisms would be present. These hypotheses will be verified through laboratory tests using the listed tests in section 2 of this paper. In this case, we are following the path of oxidation being present.

Instead of asking “Why?”, we will ask the question, “How could?” as this leads to more factual answers rather than opinions. In this case, the question of “How could oxidation occur?” will be asked. There are two main ways for this to occur, either there is the presence of oxygen and Temperature in Excess of the operating temperature or there is a Less Than Adequate (LTA) presence of Antioxidants as shown in

Figure 9 below:

Figure 9: Second part of Oxidation logic tree

Figure 9: Second part of Oxidation logic tree

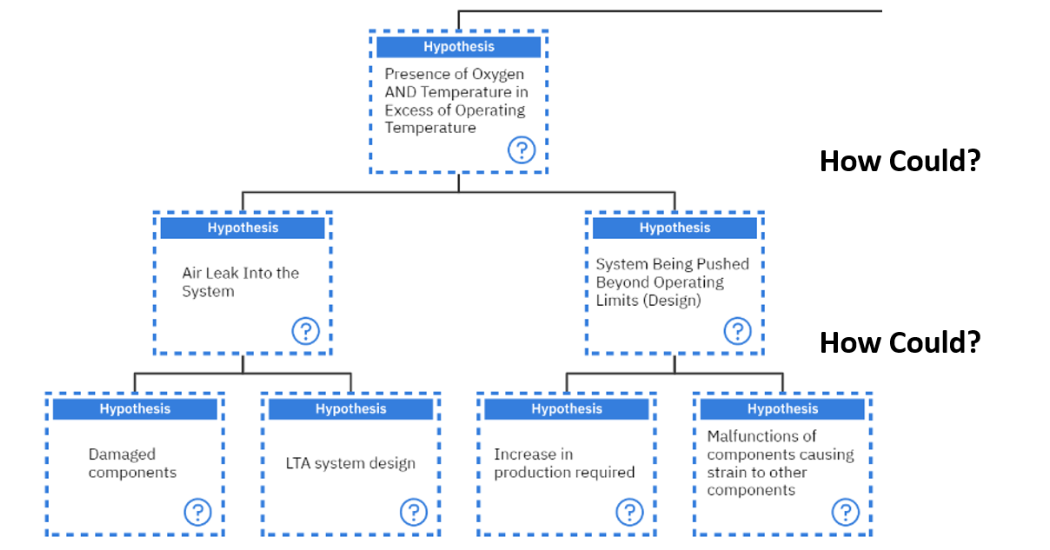

Again, the question of “How could the presence of oxygen and temperature in Excess of Operating temperature occur?” is asked. This can occur if there is an air leak into the system or if the system is being pushed beyond operating limits.

When the question of “How could there be an air leak in the system?” is asked, two main answers could be that the components are damaged or there was a Less Than Adequate system design which allowed air to enter the system. These two hypotheses should be further investigated and verified. Since these are mechanical elements, they will not be investigated in this discussion as we are focused on the lubricant degradation aspects.

On the other hand, if the question of, “How could the system be pushed beyond its operational limits?” is asked, then two suggested hypotheses can be generated. Either an increase in production was required or there were some malfunctions of components which caused strain to other components thus pushing these beyond their operational limits as seen in figure 10 below.

If an increase in production was required then this needs to be investigated with the teams involved to determine how the decision was made to increase production. This hypothesis will not be followed in this paper but should be followed during the investigation.

The team should also investigate whether malfunctions of components caused strain to other components pushing them outside of their operating limits. This is a mechanical investigation which would require some physical inspections as well as other condition monitoring tests to determine if this was indeed the case. This hypothesis will not be followed for this paper.

Figure 10: Investigating the hypothesis of, “Presence of Oxygen AND Temperature in Excess of Operating temperature”

Figure 10: Investigating the hypothesis of, “Presence of Oxygen AND Temperature in Excess of Operating temperature”

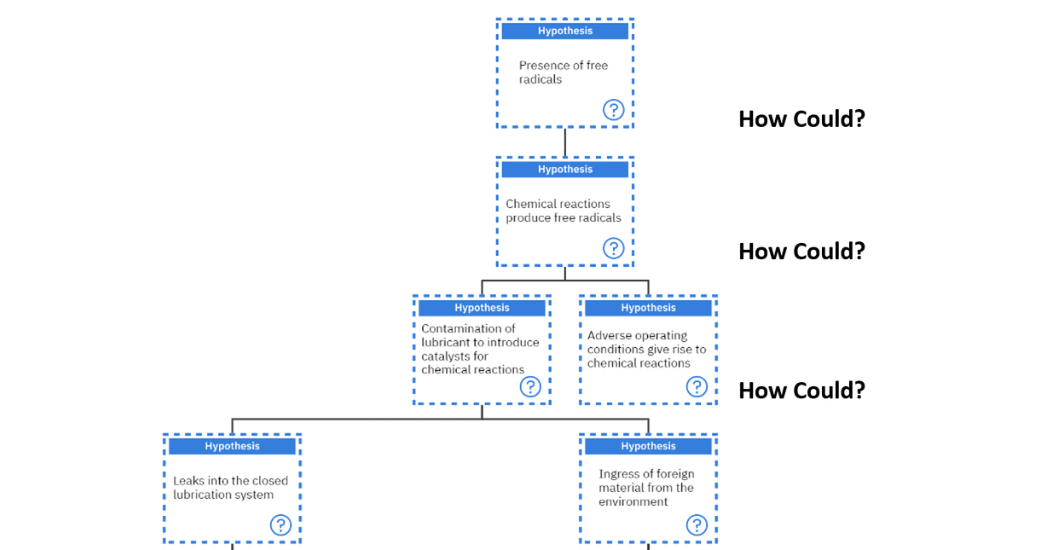

The second major hypothesis of “Less than adequate Presence of antioxidants” will now be investigated. When the “How could?” question is asked, there are two main ways, either there was a presence of free radicals or less than adequate lubricant specifications. These hypotheses will now be investigated.

“How could there be a presence of free radicals?”. These are usually produced when some chemical reaction has occurred. “How could a chemical reaction occur?”. Typically, these can occur if there was contamination of the lubricant to introduce catalysts for chemical reactions or there were some adverse operating conditions giving rise to chemical conditions.

In the case of the latter, adverse operating conditions may be the normal operating conditions of this piece of equipment. In this case, it is called a “contributing factor” and does not need to be investigated.

The question of, “How could the contamination of the lubricant to introduce catalysts for chemical reactions occur?” is asked. There are two main ways this can occur; either the contaminants came from the outside or the inside of the system. In this case, two hypotheses could be formed, which question if there were leaks into the closed lubrication system or if there was ingress of foreign material from the environment as shown in figure 11 below.

Figure 11: Investigating the hypothesis of, “LTA presence of antioxidants” – ‘Free radicals’

Figure 11: Investigating the hypothesis of, “LTA presence of antioxidants” – ‘Free radicals’

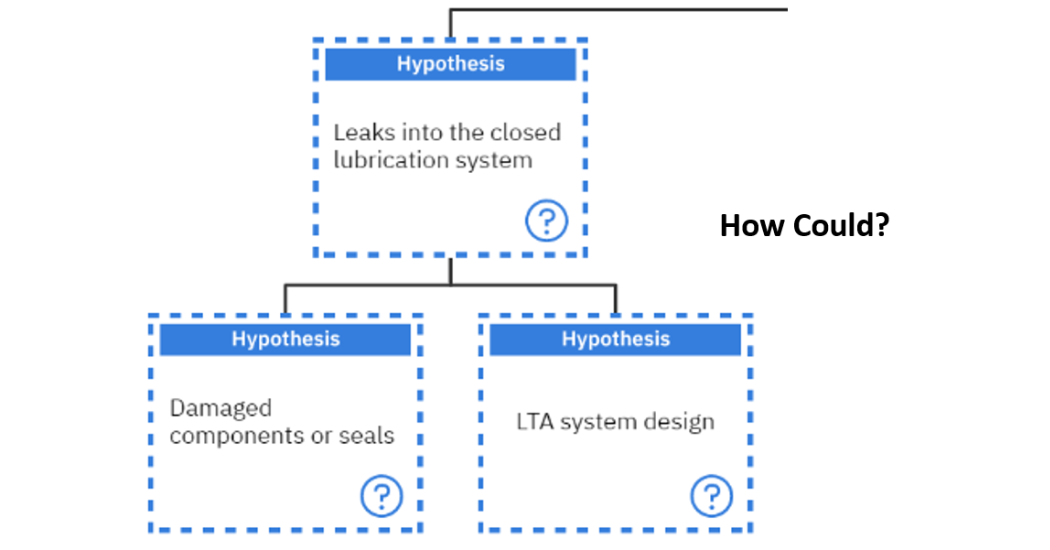

By following the hypothesis of whether there were leaks into the closed system, the question of “How could?” is asked again. In this case, two hypotheses can be formed: either there were damaged components or seals or there was a less than adequate system design which allowed leaks into the closed system as seen in figure 12.

The damaged components are a physical root cause which must be investigated and verified in this investigation. On the other hand, the LTA system design is labelled as a systemic root cause for this example.

Figure 12: Investigating the hypothesis of, “Leaks into the closed lubrication system”

Figure 12: Investigating the hypothesis of, “Leaks into the closed lubrication system”

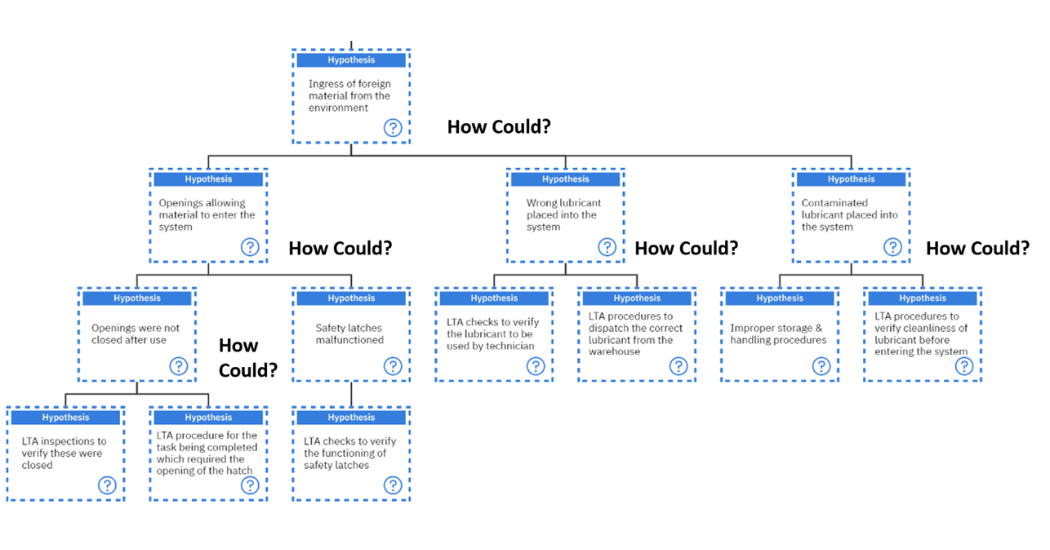

On the other hand, by asking the question of, “How could there be ingress of foreign material from the environment?”, there are three possible hypotheses. Either there were openings which allowed material into the system, or the wrong lubricant was placed into the system or contaminated lubricant was placed into the system. Each of these will be investigated.

“How could openings allow material to enter the system?”. Either the openings were not closed after use, or the safety latches malfunctioned causing them not to be closed after their use. This further prompts the question of, “How could the safety latches malfunction?” This can happen if there are less than adequate checks to verify the functioning of the safety latches which is a systemic root cause.

The question arises again “How could the opening not be closed?”. This can be as a result of less than adequate inspections to verify if these were indeed closed which is a systemic root cause or there was a less than adequate procedure for the task being completed which required the opening of the hatch which is also a systemic root cause.

Following the hypothesis of, “How could the wrong lubricant be placed in the system?”, this leads us to, less than adequate checks being used to verify if the technician is using the correct lubricant or less than adequate procedures being used to dispatch the correct lubricant from the warehouse. Neither of these are human root causes, rather systemic root causes.

Finally, on to the question of, “How could contaminated lubricant be placed in the system?”. Either there are improper storage and handling procedures which is a systemic root cause. Or there are less than adequate procedures to verify the cleanliness of the lubricant before entering the system which is also a systemic root cause covered in figure 13 below.

Figure 13: Investigating the hypothesis of “Ingress of foreign material from the environment”

Figure 13: Investigating the hypothesis of “Ingress of foreign material from the environment”

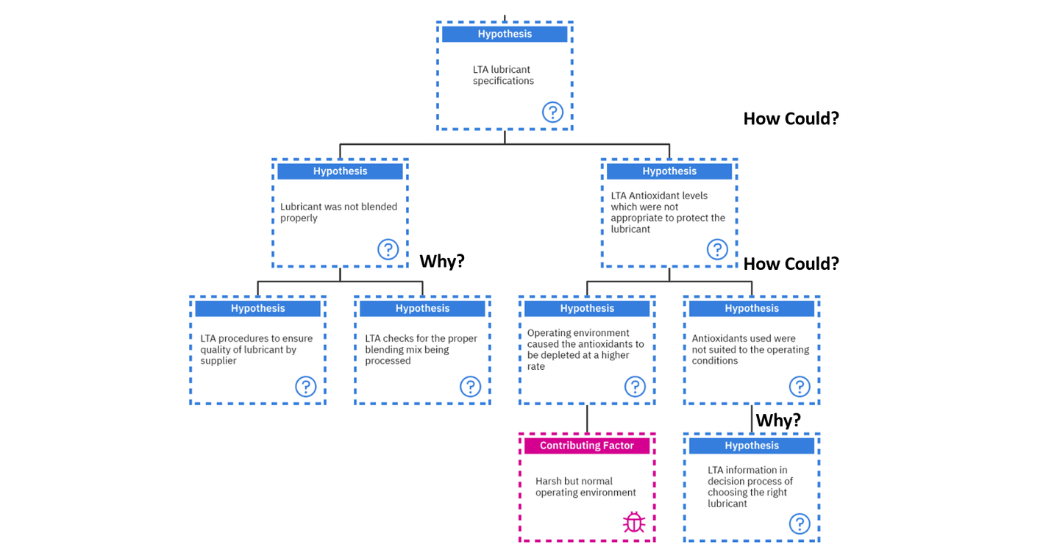

On to the last hypothesis of, “How could there be less than adequate lubricant specifications?”. This can occur if the lubricant was not blended properly or there were less than adequate antioxidant levels which were not appropriate to protect the lubricant.

“How could the lubricant not be blended properly?”. This can occur if there were less than adequate procedures to ensure the quality of the lubricant by the supplier, which is a systemic root cause and up to the supplier to investigate. Or there were less than adequate checks for the proper blending mix being processed, which is also a systemic root cause which must be investigated by the supplier.

On the other hand, “How could less than adequate antioxidant levels exist which were not appropriate to protect the lubricant?”. Either the operating environment caused the antioxidants to deplete at a faster rate which could have been as a result of a harsh operating environment. This harsh operating environment is a contributing factor of which we have no control.

Or the antioxidants used were not suited for operating conditions. How can this happen? If there was less than adequate information in the decision process of choosing the right lubricant. This can be a human root cause as a decision was taken by a human in this process to not get more information before making the final decision on the process as shown in figure 14 below.

Figure 14: Investigating the hypothesis of “LTA lubricant specifications.”

Figure 14: Investigating the hypothesis of “LTA lubricant specifications.”

FINDINGS & DISCUSSION

Each of the aforementioned mechanisms produce unique characteristics which can aid in identifying its occurrence in a lubricant. Also, as noted above, there are various lab tests for each of the mechanisms. These can help to identify if the mechanism has occurred; however, we should examine ways to avoid the mechanism from occurring. This can be done if we understand the root causes of the mechanism and investigate beyond the physical elements.

For this paper, the author developed a logic tree for the most prevalent degradation mode, oxidation. Based on the definition of how oxidation occurs from the methodology, the attached logic tree can be developed shown in figure 15.

Figure 15: Full Logic Tree for Oxidation

Figure 15: Full Logic Tree for Oxidation

Ideally, to avoid industrial lubricant degradation, one must be able to properly identify the degradation mechanism which is occurring and assess the physical, human and systemic root causes to ensure that this method of degradation does not occur again.

This is not a standardized set of root causes as each system will have unique processes or operating environments which are specific to that machine. As such, the logic tree in this example was developed as a guide to allow readers to become more familiar with the technique of finding the real root causes. Therefore, this technique can be applied to the other degradation mechanisms and by extension to other processes which require further investigation.

CONCLUSION

Quite often, industry personnel focus on the tests which can be done to identify if a degradation mechanism is occurring and then implement physical changes to the system to ensure that degradation does not happen again in the future. From the extensive logic tree developed above, it is quite clear that by stopping at the physical roots, there are still human and systemic roots which occur.

If these human and systemic roots are not properly addressed, then the degradation process will continue to occur. It is the intention of the author to shed some light on the deeper analysis which must be executed to fully understand the lubricant degradation mechanisms before addressing it and eliminating it from the system.

REFERENCES

Mathura, S. (2021). Lubrication Degradation Mechanisms – A Complete Guide. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

Livingstone, G., Wooton, D., & Ameye, J. (2015). Antioxidant Monitoring as Part of Lubricant Diagnostics – A Luxury or a Necessity?

Mathura, S., and Latino R. (2022). Lubrication Degradation – Getting into the Root Causes. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

About the Author

Sanya Mathura is an accomplished engineering professional and CEO of Strategic Reliability Solutions Ltd, a global consulting firm specializing in reliability and asset management. With over 15 years of experience, she holds a BSc in Electrical & Computer Engineering and a Master’s in Engineering Asset Management from UWI.

Sanya is internationally recognized for her expertise in lubrication and reliability engineering, being the first female in the Caribbean to achieve the ICML MLE certification and the first female globally to earn the ICML Varnish Badges (VIM & VPR) and Mobius Institute FL CAT I certification. She serves on multiple editorial and advisory boards.

A published author of several technical books and articles, she promotes knowledge-sharing across the STEAM community. As series editor of the “Empowering Women in STEM” books, she champions mentorship, representation, and collaboration among women in technical fields. Sanya is also the external steward of the EDIMC of UWI’s DECE.

Her leadership and advocacy have earned her the 2024 Engineer of the Year Award from Empowering Industry (United States). She spoke about “How do we get more women involved in Engineering and Asset Management” in Australia (2025) and has been part of the discussion panel “Women in Engineering” hosted by APETT. Sanya wrote an article “Why are there so few registered female engineers in Trinidad & Tobago” for BOETT. Through mentoring, public speaking, and educational outreach, Sanya continues to inspire women and youth across the Caribbean and beyond, demonstrating excellence, innovation, and commitment to community development in the STEAM disciplines.

UWI – University of the West Indies

ICML – International Council for Machinery Lubrication

MLE – Machinery Lubrication Engineer

VIM – Varnish & Deposit Identification and Measurement

VPR – Varnish & Deposit Prevention and Removal

FL CAT I – Field Lubrication Category I

EDIMC -Equality, Diversity & Inclusion Mainstreaming Committee

DECE – Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering

APETT – Association of Professional Engineers Trinidad and Tobago

BOETT – Board of Engineering Trinidad and Tobago